Could AI Solve the Clinician Burnout Problem?

There have been a lot of questions around the use of artificial intelligence (AI); will it lead to our extinction? Should we ban AI chatbots in classrooms? (Two CHIBE-affiliated faculty argue no.) Will it kill jobs or worsen wealth inequities?

In a recent Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics (CHIBE) external advisory board meeting, one more AI-related question emerged: burnout is crippling clinicians; could AI help?

A recent study found that 63% of physicians reported symptoms of burnout in 2021. Seeking to address this issue, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) created a National Plan for Health Workforce Wellbeing with goals like supporting mental health, creating a positive work environment, having a diverse workforce, and addressing barriers for daily work. The American Medical Association cited that burnout is often associated with “system inefficiencies, administrative burdens, and increased regulation and technology requirements.”

“The change is palpable,” said David Asch, MD, MBA, Senior Vice Dean for Strategic Initiatives in the Perelman School of Medicine and a CHIBE Internal Advisory Board member. “Clinicians are more beleaguered than they used to be, and that’s meaningful in part because they have traditionally felt empowered, rewarded, and proud of their work. Burnout’s many elements could seem more likely in less empowered professions. But if suddenly you find that people who seem to be in control of their destiny are feeling burned out, that’s news. That’s man bites dog.”

Michael Parmacek, MD, Chair of the Department of Medicine at Penn and a CHIBE Internal Advisory Board member, said he sees AI as an opportune tool to take some mundane work off the plate of providers. It could lessen some of the administrative tasks and take over the work that causes headaches for many clinicians.

“Perhaps what drives burnout more than anything is providers feeling that they are spending too much of their time doing low-value activities, things that really take away from why they became what they became in the first place,” said Dr. Parmacek, who was quick to point out that it’s not just physicians who are feeling burnout, it’s the whole team and workforce.

Dr. Parmacek’s Department was looking at burnout long before even the NAM released its report, and what their assessment found was that direct care between the provider and the patient and also high-level decision-making were two things that alleviated burnout.

“One of the misconceptions that I think the public still gets confused about is that most people think burnout is from working too hard or working too much. It turns out, that’s probably not the case,” Dr. Parmacek, the Frank Wister Thomas Professor of Medicine, said. “If you’re doing something that you think is important or that will make a difference, you’re not going to burn out, and you’re going to be excited by your work. So, it’s not just the number of hours you work, it’s how you spend your time, and reducing, or eliminating, low-value activities to combat burnout is key.”

How AI Could Potentially Help With Burnout

Dr. Parmacek mentioned there are commercial products in development that could assist with things like charting and documentation so the provider doesn’t have to spend more time documenting an encounter than time spent talking to a patient. Another time-consuming task clinicians encounter is the inbox messages they receive from patients – many of which are pretty straightforward to answer.

“There are generative AI programs that when tested and validated could answer a large percentage of those questions without the need for a provider directly answering those questions,” he said. Then, the more complicated questions can be triaged and answered directly by the provider.

Kevin Johnson, MD, MS, FAAP, FAMIA, FACMI, David L. Cohen University Professor of Pediatrics, Engineering, Biomedical Informatics, and Communication at Penn, gave the example of a patient who receives a note saying her A1C is 6.5%. She might wonder what that means, and Dr. Johnson said ChatGPT could do a great job at answering that question and providing a comprehensive summary.

“And if you further said to ChatGPT, ‘Explain it to me as if I had a reading level of third grade,’ ChatGPT will actually do that, too,” Dr. Johnson said. “So we know that, in theory, the questions patients typically ask could be addressed using large language model approaches.”

Dr. Johnson pointed out there are 4 stakeholder groups (physicians, nurses, office staff, and patients) and 6 functions in the EHR (ordering, messaging, documenting, searching, summarizing, and providing guidance), and he believes AI and machine learning could possibly help in each area for those stakeholders.

Another example of a headache for providers is dealing with prior authorization and needing to justify prescribing a medication or a test or scan to insurance companies. In theory, AI could scan a chart and fill in the information required to receive preauthorization for medications, procedures, or other services. This would save the provider a lot of time.

“Allow the provider to do what they like to do, which is deal with the complexity of the patient directly,” Dr. Parmacek said.

Judith Long, MD, Chief of the Division of General Internal Medicine and a CHIBE affiliate, is also hopeful that AI can alleviate mundane tasks from providers.

“The InBasket is such a burden, and I think quite a bit of the work could be addressed automatically or with AI and decision support,” she said. “The key will be making sure AI is not compromising clinical care or relationships.”

Dr. Long thought back to the first days of credit card companies using automated responses over the phone.

“The systems were clunky and unreliable, and I would just say ‘talk to a human’ until I got a human because I did not trust the system,” said Dr. Long. “Then I said ‘talk to a human’ because the automated responses usually did not deal with my request. Now, I not only trust the systems, but also most of my concerns can be addressed quickly and automatically. I think it will take time to perfect these systems, but they could help address provider burnout. If AI can alleviate the need to type, even better. The other appeal is that AI could be cheap. I can already solve some of these issues with human power, but the cost is not feasible.”

Anish K Agarwal, MD, MPH, MS, Assistant Professor and Chief Wellness Officer in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Penn and Deputy Director of the Center for Digital Health, said he would also love to see AI address the burden of patient messaging.

“There is a tremendous amount of back-and-forth portal messaging that may be related to appointments, follow-ups, insurance, and clinical questions,” Dr. Agarwal said. “The reality is that much of this could potentially be managed more efficiently with AI to help properly sort, distribute, and perhaps even answer the bulk of these messages. This would help reduce the amount of time clinicians are spending in front of their computers and working from home. It could finally work to take things off their plate and free that time up for better patient care and for time to rest and recover when they aren’t at work. Additionally, a lot of clinician time is spent trying to get patients to the right place and navigating logistics related to prior authorizations, scheduling, and sorting through large amounts of paperwork and clinical data. The future of AI could help condense the amount of human time needed to address the nuances of getting people to the right care at the right time.”

Reservations with AI

Dr. Parmacek said we’re in an “AI intellectual puzzle” right now, where everyone thinks AI will solve every problem or at the other extreme AI could make humans extinct.

“I think we have to be very, very cautious about saying AI is the answer to all our questions,” Dr. Parmacek said. “I think it’s nowhere near as easy as many would have you believe, but AI does have great potential if tested, validated, and applied in the right setting to the right questions.”

Two other important issues that need to be addressed before AI should be applied in the clinical setting are protecting patient privacy and avoiding amplification of bias that is already in medicine, Dr. Parmacek said. He gave the example of chest pain in women. For years, providers have consistently thought that when a man and a woman present with the same kind of chest pain, they think it’s more serious in the male patient.

“That sort of bias gets amplified by AI by repeating the same mistakes we’ve made before and then amplifying them,” he said. “We have to find ways to recognize bias and protect against it.”

Dr. Long pointed out that there will be unintended consequences of using AI, and she noted the potential for new technology to affect jobs.

“There are always unintended consequences from new technology. I have not talked to a travel agent in over 25 years. There is a lot to worry about with AI, but there is also a lot of promise,” she said.

Many clinicians were also sold on how great the digitalization of electronic records was going to be for them, Dr. Asch said, but not everyone appreciated how much it would come with other challenges. Likewise, he thinks some clinicians hear the hype of AI and can think of cool ways to use it, but others may not be so quick to embrace it.

“Others may think, ‘OMG, here’s another example of something that is purported to be in my best interest, but it’s really yet another way to be tortured,” Dr. Asch said.

In addition, the more we delve into the clinical sphere of automation, the more dangerous misinformation (and the ability to amplify misinformation — or Dr. Johnson would call it “disinformation”) will be, so we should put work into protecting people from that, Dr. Asch said. He also finds it interesting that some AI experts are talking in doomsday scenarios about the end of the world. Initially, he wasn’t so nervous about AI, but hearing experts talk about “extinction” gave him pause.

“It’s like when your surgeon tells you that they don’t think surgery is a good idea. You believe that surgeon, right? Any surgeon who doesn’t want to operate probably has a very good reason not to operate. So, when some AI expert tells you that AI is dangerous, I think I should believe that,” he said.

“My reservations with AI are similar to my reservations with anything in medicine or life really—nothing is absolute and to take things in moderation,” Dr. Agarwal said. “AI can’t solve or replace the human intuition or touch. While we can’t, nor shouldn’t, try to get AI to solve things like complex diagnostics or patient visits with their doctor, we can use it for what it is: a tool. All tools, much like a hammer, are meant for certain things but won’t work for everything. In my opinion, AI should be used to offload clinicians from tasks that take them away from treating their patients. It shouldn’t replace human care.”

Dr. Johnson, who describes himself as an early adopter with a healthy degree of skepticism, called for more studies into AI and for more research into the relative cost of generative AI. (One thing people may not be aware of is the large carbon footprint of AI.)

“The AI that we have right now is absolutely inspiring us to do more studies and to generate new hypotheses,” said Dr. Johnson. “Like any good scientist, those of us in health care should now be thinking about doing hypothesis testing – can we actually demonstrate that what AI is doing is both cost effective and mitigating burnout?”

How Behavioral Economics Fits Into This Discussion

Dr. Asch said behavioral economics can be leveraged to help with this issue of clinician burnout, and it may not even require AI.

“What behavioral economics does is recognize people’s irrationality,” Dr. Asch said. “And the solutions to that are often either to debias them, or to harness the irrationality, or to bypass the irrationality.”

Defaults, he pointed out, are a way to harness irrationality. Rather than encouraging a type of thinking, defaults can be used to bypass the thinking, in a way. If there’s an issue that a doctor has trouble with, one way to manage that is to bypass the doctor and involve a different type of clinician – a nurse or a pharmacist – to handle it.

“That’s kind of behavioral economic response, which is just take them out of the loop,” Dr. Asch said.

So, some problems could be solved by taking some humans out of the loop and replacing them with other humans, or you can take all humans out of the loop and involve automated algorithms in their place, he said. An AI system could also have different levels of engagement too; maybe the system tells the clinician, “This patient could benefit from a statin,” or the system could order the statin, but there’s an opt-out option. Dr. Asch said we should recognize that computers may be able to do some things better than clinicians because the systems don’t have the same psychological foibles.

Other Considerations

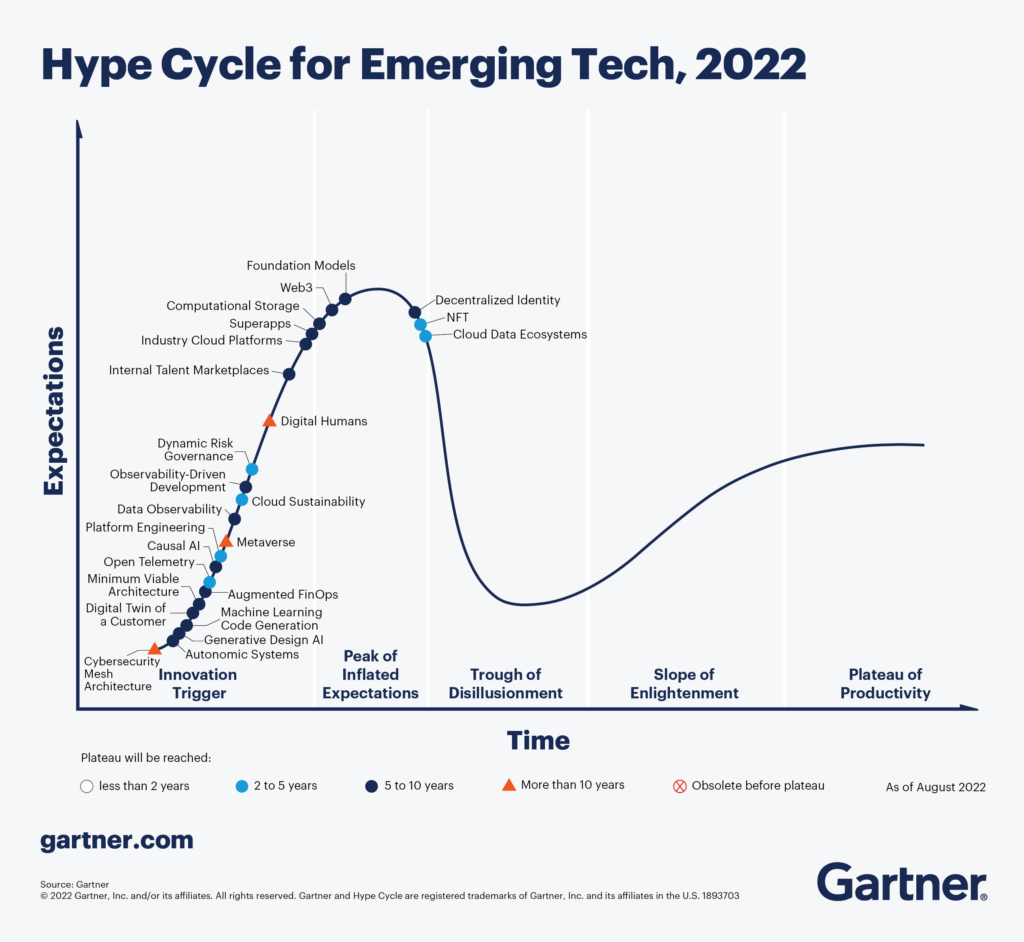

Dr. Johnson cited the Gartner Hype Cycle, which is a graphic representation of our response to a new technology over time, with “expectations” on the y axis and “time” on the x axis. Technology often follows this path of innovation trigger, peak of inflated expectations, trough of disillusionment, slope of enlightenment, and plateau of productivity, where the technology goes mainstream. Right now, he thinks of the AI experts who say AI is as risky as pandemics and nuclear war are in the trough of disillusionment, but he expects AI to follow a similar path to the plateau of productivity.

Dr. Agarwal made an important point that if AI can help take some burdens off of clinicians, those providers should be able to keep that time for themselves.

“I believe if we are going to really invest in treating burnout, then if and when AI helps us free up time for clinicians, we should give that time back to clinicians,” Dr. Agarwal said. “We should resist the urge to fill that time with more work, rather, let’s use AI to give time back to the clinicians to cultivate their careers, be with their families, and support a longer and healthier practice.”