The Evidence on Health Behavior Incentives in State Medicaid Programs

AcademyHealth Panel Rounds Up the Research

As a number of states experiment with health incentives as an element of their Medicaid programs, researchers are analyzing the results with an eye towards informing future evidence-based policies. At this week’s AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting, CHIBE affiliated faculty member Charlene Wong, MD led a panel in which investigators discussed the latest evidence on the impact of these incentives on healthy behaviors among Medicaid beneficiaries.

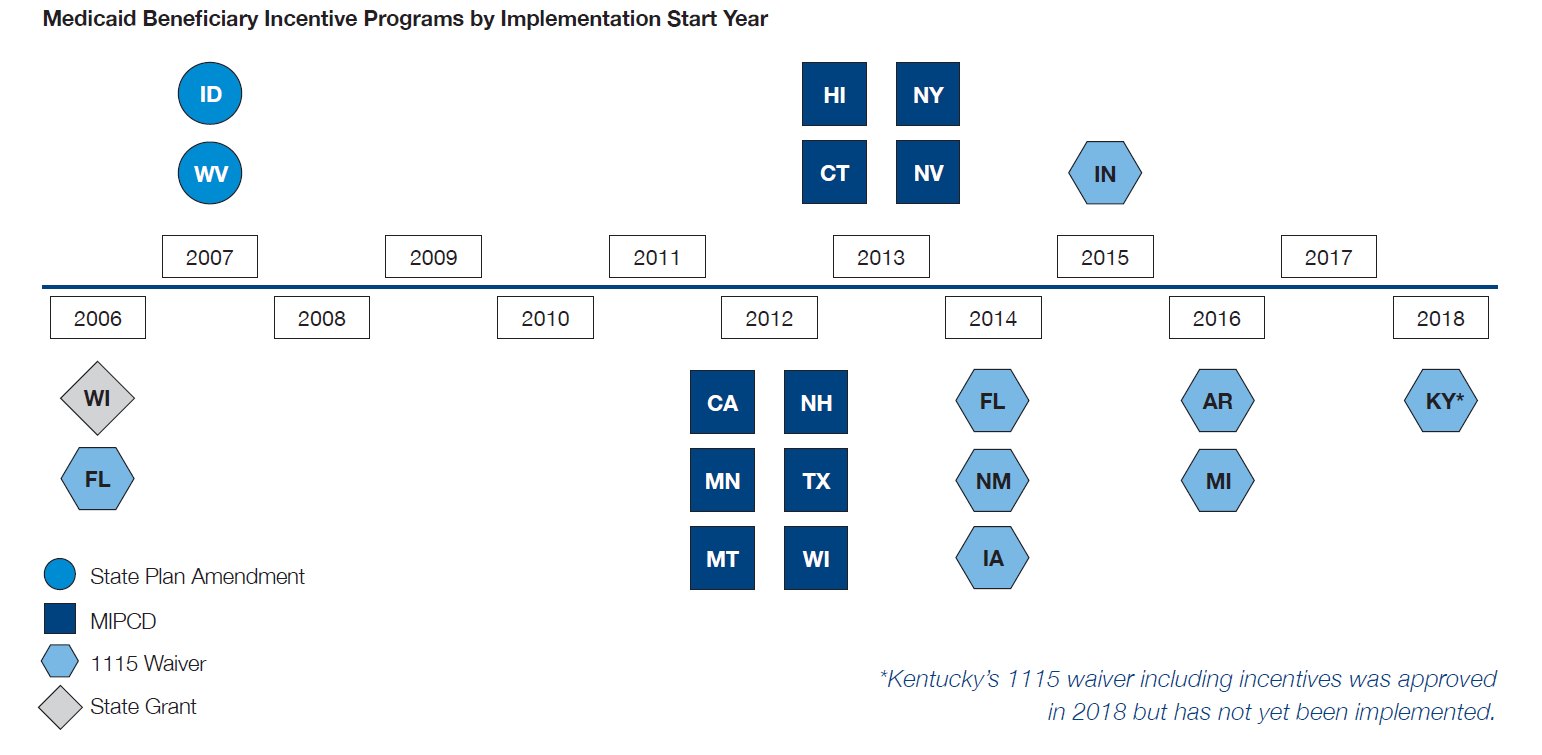

The panel began with a presentation by Rob Saunders, PhD of the Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy. Saunders and his colleagues, including Dr. Wong, recently authored an issue brief reviewing evidence from eighteen states that have implemented a health incentive program among their Medicaid population (excluding Managed Care Organization programs). Saunders noted that these programs have evolved over time, starting with early state incentive programs focused on rewards for one-time preventive health activities and evolving into more recent Section 1115 waiver programs, which tend to feature both carrot and stick elements aimed at reducing chronic disease.

highlighting how the policy levers to implement these programs has changed over time.

Findings from a literature review and interviews with numerous stakeholders were mixed. Saunders noted that beneficiary awareness of incentive programs is low to moderate, a challenge highlighted by other members of the panel. Additionally, while some programs were successful at changing participant behavior, those targeting smoking cessation had the greatest impact. Programs aimed at increasing the use of preventive services had more varied results. Strikingly, no clinically significant improvements in chronic disease outcomes were found among beneficiaries. The report noted that few evaluations have been performed to examine the impact of health incentive programs on Medicaid expenditures. Saunders emphasized the high administrative burden of state incentive programs, and suggested that aligning clinician incentives with other payment reforms could ease some of that burden.

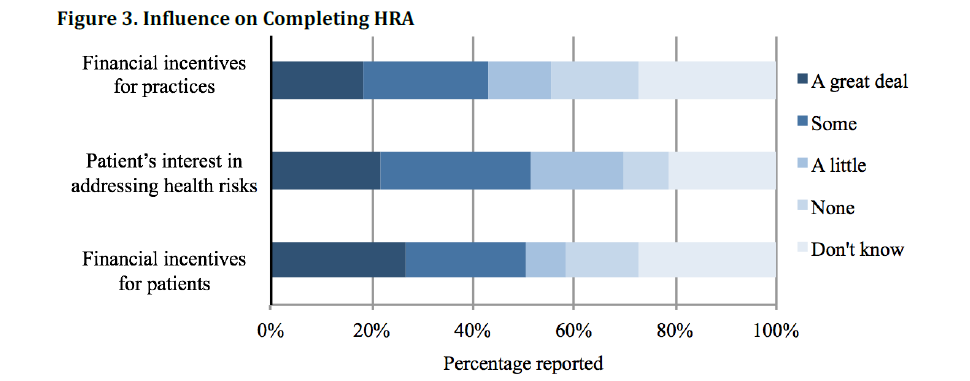

At the University of Michigan’s Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, Susan Goold, MD, MHSA, MA surveyed Medicaid enrollees and primary care practitioners about the Healthy Michigan Plan, the state’s Medicaid incentive program implemented as part of a Section 1115 waiver. The program provides a gift card incentive for patients that complete a Health Risk Assessment (HRA) and additional financial incentives to clinics for patient completion of HRAs. Goold surveyed program participants on the impact of the incentives on patient and provider decisions to complete an HRA.

Consistent with Saunders’ report, Goold found that beneficiaries’ awareness of the program was low. In fact, most Michigan Medicaid beneficiaries did not realize that completing an HRA would result in a financial reward. Among those who were aware of the reward program, many did not realize the reward was financial, instead believing the “reward” was improved health. Interviews with patients and providers who completed HRAs found that each group downplayed the role of incentives in their decision-making. Instead, patients frequently cited their provider’s encouragement as the main reason they chose to complete an HRA, while providers cited their patients’ health goals.

The evidence in Michigan underscores the need for more effective communication to educate Medicaid beneficiaries about health incentive programs. Meanwhile, the “Breathe Well, Live Well” program in New Hampshire highlighted the success of financial incentives in the context of smoking cessation. Mary Brunette, MD of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services evaluated the program through a clinical trial, the New Hampshire Incentives for Healthy Behavior Study. Her study examined whether abstinence-contingent financial incentives improved outcomes among adults with serious mental illness when added to smoking cessation treatments at community mental health centers. Brunette concluded that participants who received monetary incentives were significantly more likely to maintain smoking abstinence over time than those that received tobacco treatments alone.

Dr. Brunette noted several practical considerations for other states to consider when implementing Medicaid health incentive programs. First, it is critical to engage both state Department of Health and Human Services administration and health system administration to secure funding and overcome the administrative hurdles necessary to successfully implement these programs. Second, Brunette noted that incentives typically have the highest impact when they are immediate and salient, factoring in the behavioral economic principle of temporal discounting. Finally, she suggested that sustained behavior change is facilitated through incentives that grow over time.

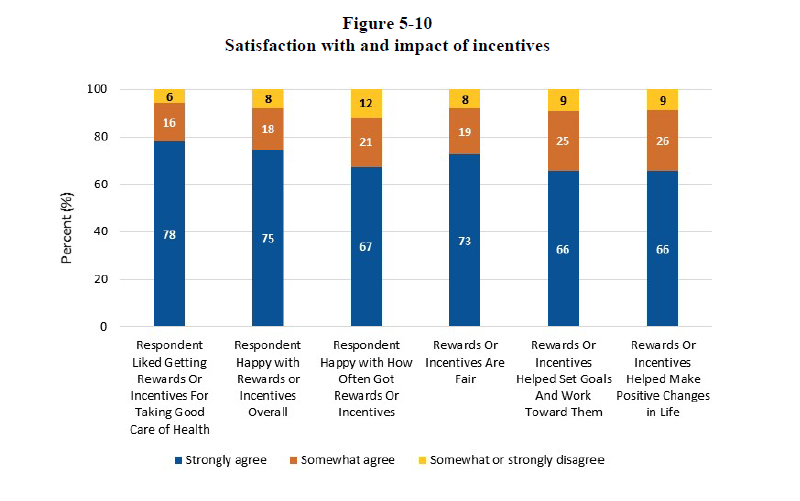

To cap off the session, Thomas Hoerger, PhD of RTI International presented his evaluation of the Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Disease program, which was established in Section 4108 of the Affordable Care Act and implemented in states both with and without Medicaid expansion. The mixed-methods five-year evaluation examined states with varying incentive schemes, with rewards ranging from $50 to $1150 annually, and behavior change most frequently aimed at smoking cessation and diabetes prevention.

The incentive programs analyzed by Hoerger led to significantly higher uptake of preventive services, including diabetes education and provider visits. Participants also showed small, though not always significant, improvements in health. However, there was no significant impact on use of other Medicaid-covered services, and Medicaid expenditures per-enrollee were not significantly affected by the program. Despite this, Hoerger found overall program satisfaction was high, and participants believed the program helped them on the path to achieving their health goals. While all states successfully implemented their programs, Hoerger found that administration was complex and costly, as noted by Saunders.

All panelists pointed to the need for further research examining how to optimally leverage health incentives as a part of state Medicaid programs. Hoerger suggested that, even with the most well-designed incentive program, policymakers should not expect “miracles.” Goals such as smoking cessation and weight loss are extremely challenging to attain in any patient population. Tackling these health issues among Medicaid beneficiaries can be even more challenging given the many competing demands individuals enrolled in Medicaid face. Members of the audience highlighted the need for an increased focus on the use of incentives in connection with social determinants of health outside the clinical setting.