NEJM Catalyst: Key Insights on Launching a Nudge Unit within a Health Care System

By Sujatha Changolkar, David A. Asch, MD, MBA, Mohan Balachandran, MA, MS, Kevin G. Volpp, MD, PhD & Mitesh S. Patel, MD, MBA

Even the most informed and resourced clinicians deliver health care with gaps — overusing surveillance imaging in a patient with cancer, failing to prescribe statins to a patient who meets the guidelines for them, or prescribing an expensive drug when a less expensive equivalent is available. Typically, these gaps are created not because of some error of judgment or knowledge or bad intentions, but because doing everything right all the time is difficult and often the design of practice environments inadvertently makes guideline-concordant care harder — or at least doesn’t make it as easy as it could be.

The practice environment influences the decisions that clinicians make. If it is easier to prescribe brand-name drugs because they are easier to remember, or first on the menu, then more brand-name drugs will be prescribed. If the default process is to get vital signs every 6 hours, then vital signs will be checked every 6 hours, even if every 12 hours would be sufficient and might let patients sleep more. Recognizing that many of our routine practices are influenced by the nature in which choices are presented to clinicians, health systems have been considering the formation of a nudge unit or behavioral design team to make higher-value choices easier to make.

Nudges are subtle changes to choice architecture that can have an outsized impact on medical decision-making. This could include changes to the electronic health record, such as setting the default option to the preferred setting, prompting clinicians to make an active choice, and making the advantages of particular choices more salient through efforts such as framing information through transparency or peer comparison feedback.

Some of these changes seem straightforward, but change is difficult, and change in the matrixed environment of health care — where technical expertise is diffused — is particularly challenging. Even health systems launching nudge units face operational challenges, and sometimes political challenges. These efforts require support from executive leadership including clinical care and information technology. Institutions may often lack expertise in behavioral economics, experimental design, innovation, or outcome evaluation. Forming a behavioral design team may also require staff with experience working with electronic health records, clinical data, and statistical analysis.

Collaborative Efforts

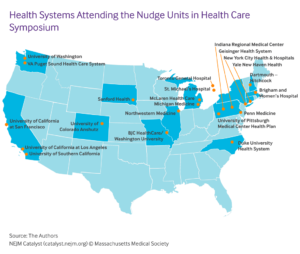

In 2016, our group launched the Penn Medicine Nudge Unit, which we believe to be the world’s first behavioral design team embedded within the operations of a health system. Our experiences have revealed some important insights that could be shared with other health systems. To disseminate these lessons and to better understand ways to address common barriers, we hosted the Inaugural Nudge Units in Health Care Symposium at the University of Pennsylvania in September 2018. Executives and researchers from 22 health systems across the United States and Canada attended.

The goals of the symposium were to assemble and share insights with stakeholders from institutions that have launched or are interested in launching a nudge unit with their health system, and to engage in a design session to help programs outline important next steps at their health system.

The symposium began with a series of talks including lessons from the Penn Medicine Nudge Unit, a question-and-answer session with Penn Medicine executive leadership, and a keynote by Cass Sunstein, coauthor of the book Nudge. Attendees then engaged in a 3-hour design session focused on the steps to implementing nudges in health care. Groups were encouraged to focus on the process of implementing nudges rather than the design of a single specific nudge. To guide them through this process, they were asked the following questions:

- What steps should be taken to identify opportunities to address this challenge?

- Now that you’ve come up with ways to identify ideas, how will you prioritize which ideas to target first?

- How will you use data to assess the current state of the problem?

- Who are the important stakeholders in this process, and how will you get their buy-in?

- How will you implement the nudge in a way that allows you to evaluate its impact?

Common Themes

After the symposium, our team collected all the insights generated and summarized the common themes. Commonly reported themes included the importance of focusing first on understanding the problem, evaluating feasibility when prioritizing opportunities, engaging important stakeholders directly and indirectly related to the decisions, and coordinating planning implementation and analysis in phases to iterate the design for maximal success before broader deployment.

To help health systems launch nudges units more quickly and with higher chances of success, we proposed a concept for a Nudge Unit Collaborative. In addition to creating a network of institutions focused on implementing nudges units to improve health care, the concept included a technology platform with a library of previously implemented nudges, coding guides for electronic health record implementation, and de-identified data to grow community-generated insights. The attendees then participated in a design session using their previously assigned groups to identify their current barriers and how a collaborative could help address them. The questions posed were:

- What opportunities exist for a collaborative to provide value for your health system over the longer term? Participants cited the potential for a collaborative to provide ongoing operational guidance and to enable multi-site collaborations across diverse institutions.

- What challenges might your health system face with launching a nudge unit that a collaborative could help to address? Participants suggested opportunities to overcome challenges, such as facilitating resource sharing (e.g., ideas, methodology) among health systems and building a library of successes and failures to help forecast ROIs.

- What are some broader contributions that a collaborative of this type could have beyond that of a single health system? Participants envisioned the opportunity to build evidence to catalyze changes in health policy, to advance the science of medical decision-making, and to transform the culture within health systems to include more systematic experimentation and dissemination of insights.

Creating the Framework

Insights from the Nudge Units in Health Care Symposium can be used as a framework for institutions to develop and launch behavioral design teams within their own health systems. As leaders face innumerable difficulties in the health care environment, the growth of nudge units creates real opportunities to change medical decision-making at the point of care through relatively subtle changes to the organization’s choice architecture. But as they try to overcome the challenges of design and implementation of a nudge unit, many health systems face obstacles in getting things started and often lack of expertise in behavioral economics and pragmatic implementation.

The important steps to successfully implementing nudges include identifying and prioritizing opportunities, engaging a broad range of stakeholders (particularly clinicians and those who lead information systems), implementing well-designed behavioral interventions paired with rigorous evaluations, and disseminating key insights more broadly. Individual organizations should welcome the value of the collaborative model to share best practices and lessons learned.